Ben Tallon: “Designers must embrace idiosyncrasies to reach their potential”

As part of his new series reflecting on the nature of creativity, illustrator and author Ben Tallon considers the creative’s psyche and what personal acceptance looks like, even if it is unconventional.

People can spend an entire life without much of an understanding about why they are the way they are. ‘Be yourself’ is something of a paradox, isn’t it? Simultaneously delightfully simple and head-splittingly complex advice. Even those of us who stride confidently ahead, dripping with an envy-inducing identity cannot always explain how they do it. That’s fine.

I have a print on my kitchen wall by former HBO and WWE designer Kyla Paolucci. It features a naively line drawn horizon characterised by imposing mountains. Dominating the sky above them, accounting for the upper two-thirds of the piece is a hand-lettered speech bubble that bellows, ‘IT FELT RIGHT.’ I sometimes stare at it and allow comical, speculative scenarios that might have conjured those words to play out in my mind, but really, it’s the limitless ownership of the words that makes it so special to me.

I have friends who are deep into neuroscience literature. Others who charge around like frustrated bulls and laugh about being this way without knowing how to explain it. I reside largely in the latter category, but as I get older and spend more time observing creativity, I become more fascinated by the science of it. I know myself well enough to accept that I am able to retain very little of the juicy segments of scientific information people share with me. Their findings help me to understand certain human behaviours, but in the same way that school’s unbalanced prioritisation of academic intelligence – a big chunk of which is about retaining and regurgitating numerical and linguistic information – overwhelmed my brain, I am found embarrassingly wanting when it comes to the onward sharing of the thing that got me all excited just ten minutes ago.

“Understanding and harnessing the creative personality”

I also know enough about myself to know that I am not stupid. This took time. Such was the glorification of grades and retaining information in school that the notion of idiocy I left with had burrowed pretty deep. It took a series of patient, gifted, kind mentors to undo this by teaching me that there is also great value in the many other forms of intelligence, the ones that enable society to function (and in many cases still contribute to the economy). It’s vital that we get to grips with this if we are to understand and harness the creative personality type.

Creativity is built, perhaps more than any other trait, on feeling. Personality is hewn from great rocks that were already there, but have been shaped by nurture, our experiences and encounters in life. Given that we each possess an invaluable unique story, no two people will share exactly the same sense of creativity.

When urged to lean into ‘what feels right,’ just like being told to be who we are, it jars because feeling is comprised of instincts and emotions that do not tend to manifest as well as language.

My own ability to articulate the way I am is basic. Haphazard, passionate, driven, devoid of common sense, observant, kind, are a few terms I’m certain would fit. My creativity, therefore my professional direction and daily decision making must be sympathetic to these if I am to remain energised and fulfilled. The same is true of everyone. For creativity to happen, there must be a certain freedom to trust in instinct and step into the unknown based on feeling. Not all of human decision making can be quantified before it happens.

How “who I am” affects my creativity

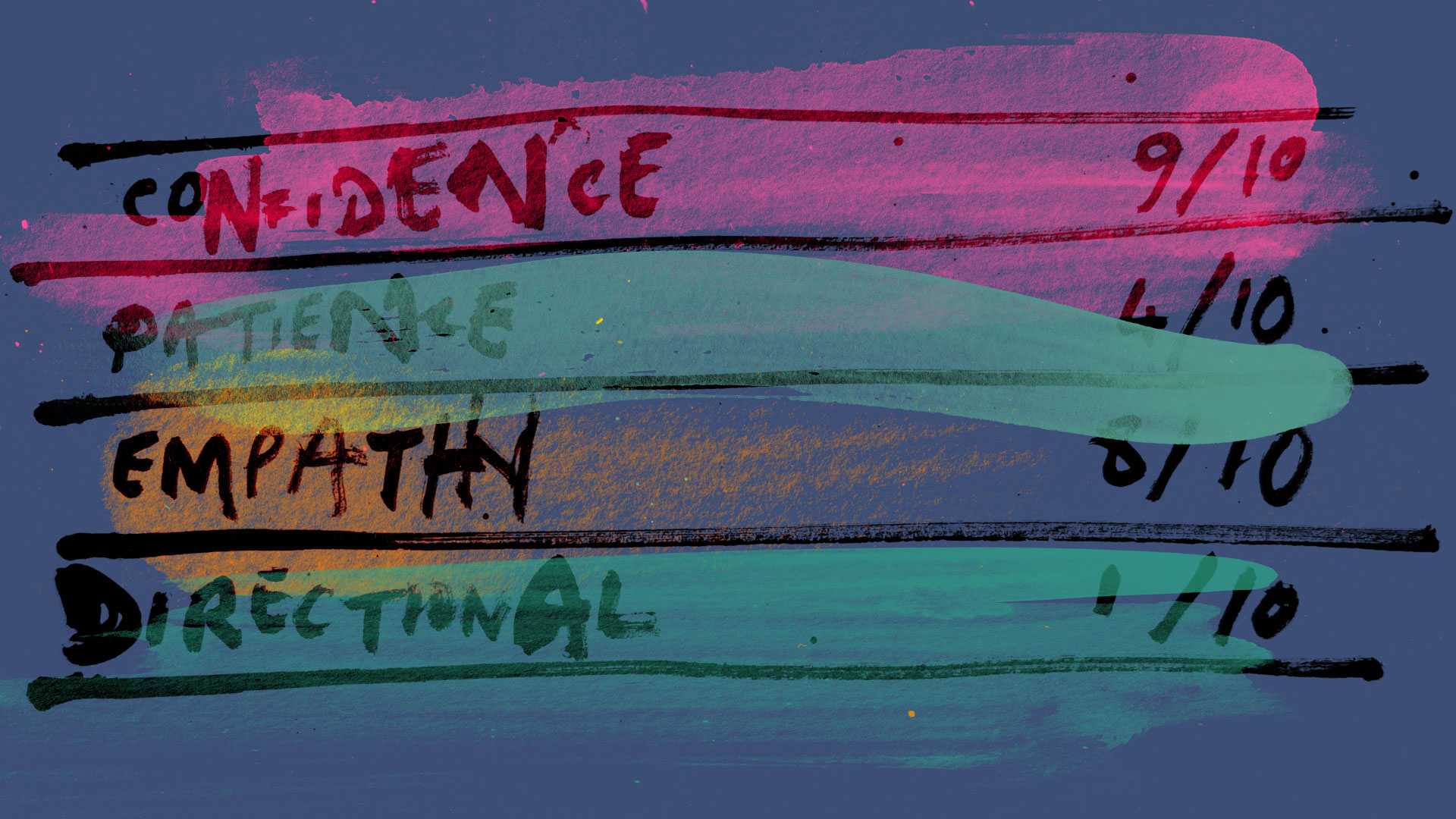

In a recent effort to create a more sustainable way of understanding the broader puzzle of who I am, I turned to simple gaming models. As a child I played Top Trumps – a card game that could be adapted to whatever your thing was – they offered Star Wars, WWE and even a version specifically ranking key moments in the life of Queen Elizabeth II.

While I wouldn’t score too highly on ‘Uniting the nation,’ I found that no matter how I scored on more relevant traits, considering each one as a potential positive and negative characteristic enabled me to gain far better control of every component.

If we’re to get into the Jungian psychology of all this – basically the assimilation of the conscious and unconscious dark and light within as a basis for good mental health – then there’s a lot of further reading to be done. But in my case I recognised that while my irritating clumsiness, perhaps a negative tendency, might score 2/10 owing to its impact in the home, it is in fact the foundation of my natural drawing style – a key part of my identity as an illustrator, a frenetic, chaotic image-making style that has won me clients including The New York Times, EMI, Channel 4 and The Premier League. Not bad for a 2/10 trait.

To go the other way, my drive has always been high. I struggle to switch off from my creativity. This must be managed and while in a Top Trump ranking system it might be 8/10 or even 9/10, if allowed to roam unchecked, I can quickly burn out, rush things and suffer from a lack of focus.

With acceptance of this duality, I am better prepared to shape my creativity to what is required of me on any given day.

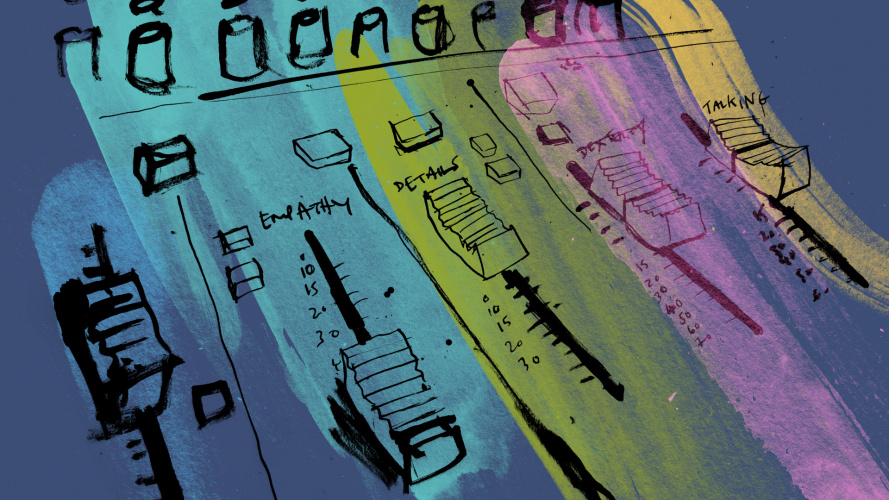

Illustrator and language teacher Sara Coggin explains her own version of my gamified personality map: “I think of it as a mixing desk. You’d have lead guitar, bass, treble, and whatever else, and the producer can turn them up and down to achieve a desired outcome.

“On mine I have strengths and weaknesses, but it can be as big as you like. There will be traits on there that you don’t often use, and it can change. You can add things in as you go through life and better understand what’s within. Then you can start to consider things in different ways, try interesting combinations. I would recommend that exercise to anyone.”

Ultimately, I try not to spend too much time introspecting. Rather, within the parameters of the demands of my schedule, finances and broader life, I pay attention to feelings and instincts, observing and learning from what happens, harnessing the good, re-shaping the unstructured and eliminating the bad. Designers must embrace their idiosyncrasies to reach their best potential. Artistic expression is the polar opposite of intelligence, if looked at through the filter of the academic models we revert to due to learned behaviours. While theory is fascinating and still valuable, if always prioritised at the cost of feeling, it can stifle something primal and pure, and stop us from being ourselves.

Source: designweek.co.uk