“Ferocious ambition”: the evolution of Benjamin Hubert’s design career

A new book written by Max Fraser shows how Hubert hacked established systems to give himself the best chance of success.

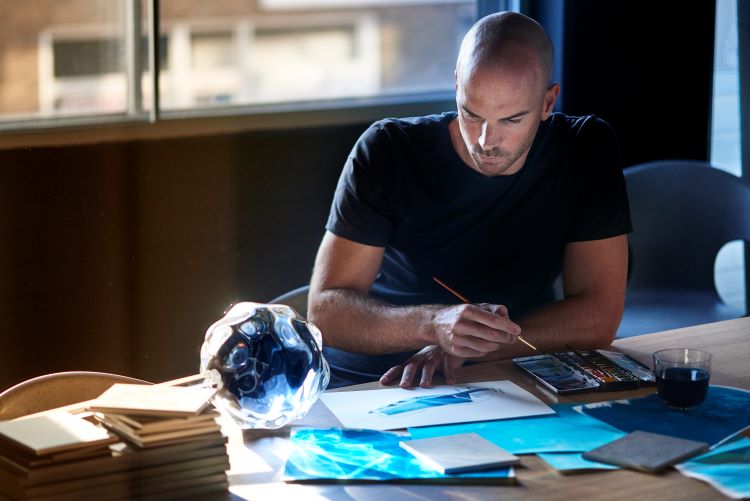

Benjamin Hubert started his Loughborough University course under the impression that he would be studying vehicle design only to find out that he had enrolled onto a furniture and product design course, which did not cover automotive design at all. Now, 20 years later, he runs design studio Layer and works with clients across the globe on multidisciplinary projects.

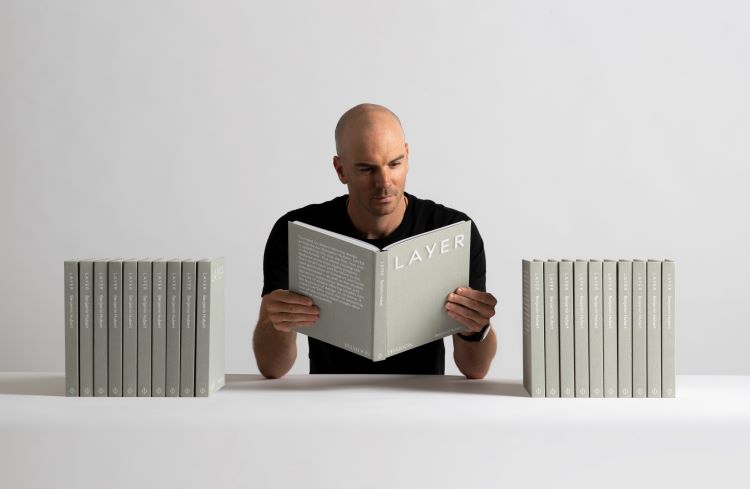

A new monograph written by design writer and consultant Max Fraser delves into everything that happened between then and now and seeks to offer advice to those coming into the design business.

Fraser acknowledges how unusual it is that someone of Hubert’s generation is “worthy of a coffee table book”. He adds that, from an author’s point of view, “writing about someone who is only ten-fifteen years in the game and has a lot more to give” presents its challenges. Despite this, he believes that documenting tales of Hubert’s “deliberate strategies” and “ferocious ambition” will help young designers understand how to thrive in an increasingly competitive industry.

Going it alone

After university, Hubert came to London to be “taken more seriously and be nearer to the action”, says Fraser, which he thinks is a “sad reality” that most designers face given resources disproportionately favour the capital.

But, just three years later in 2009 after working at design firms like Seymourpowell and Tangerine, Hubert decided to go independent with £2,000 in the bank and only a few royalty-based commissions. Fraser says that a driving factor behind this risky change was that Hubert “got quickly frustrated working for other people because he likes to be in control”.

Control for Hubert means “being fastidious about the process, paying attention to every detail and making sure the client relationship is right”, according to Fraser who adds that Hubert always prioritises good relationships with his staff and clients, so is not controlling in this sense.

Though Hubert’s control sometimes seems to be a vice, Fraser says that it contributed to his ambition and “increased his confidence”, especially when he went solo. According to Fraser, Hubert was working alone from his Leamington Spa bedroom but “projected himself to be much bigger than he was”, always using language like “we” to imply that he had a team behind him.

Having grown up alongside the generation of online media Hubert also made a conscious effort to “package his projects” in a way that was “very easy for those platforms to digest” Fraser explains. As a result, Hubert’s early work managed to get good media exposure.

Building a client base

The three years spent working at big London studios was “part of Hubert’s learning process” and gave him an “inside track” on how it all worked, not just in the field of design but also in how they promoted and marketed their work, says Fraser. Still, without the backing of a big studio name, Hubert had to find creative ways to get himself noticed across the industry.

Fraser notes that there is often a fear on the client’s side of taking on a new designer and they can ask questions like “what have you done before?” and “who are you working with already?”.

Hubert continued with his previous strategy of making himself seem “bigger and more important” by telling potential clients that he was “in conversation with” other reputable brands, even if it was still in its early stages, according to Fraser. Once he had created enough momentum with this tactic, companies started to approach him. “He was never lying,” says Fraser, “just extending the truth, which worked for him in the end.”

With interests piqued, Hubert set his sights on the 2011 Salone del Mobile in Milan and managed to release nine different products all at once. “Wherever people went they felt like they were seeing new products by this new designer Benjamin Hubert,” says Fraser. Again, Hubert was trying to play into the hands of the media, as they naturally gravitated towards whoever was making the biggest splash.

When he founded Layer in 2015, Fraser says that Hubert put equal importance on “building a respectable client base”, as it would lay the foundations for the studio’s future.

Taking his name off the door

Fraser says that one of Hubert’s main professional goals was to “humanise the world of industrial design”. Ironically, this meant taking his own name off the door in 2015, launching as the more anonymous Layer at London Design Festival.

Describing the change as a “seismic shift” in Hubert’s career, Fraser explains that one of Hubert’s main “frustrations” was that he was creating “very authored products” which is much more common in furniture and product design. He adds that manufacturers often want to “hook the designers name to it as a marketing exercise”. Wanting to be “cast in a different light” and take his studio in a more “ambitious global direction”, Hubert decided that his name had to go.

Fraser adds, “There are still clients that want to hook Benjamin Hubert to a product because Layer is such an anonymous name, but in the industrial world companies care much less about it.”

Losing the name above the door had the added benefit of allowing his staff to flourish as the studio grew. “He’s always keen to credit his team where possible and give them a degree of autonomy so they can thrive with his direction. It’s another part of creating the right environment”, Fraser says.

The world doesn’t need any more chairs”

At one stage in his career, Hubert was fighting to be seen at Salone del Mobile but, after he started his own studio, his rejection of the “commercial imperative” began, triggered by a desire to “work on projects with more meaning”, says Fraser.

“In many respects [Milan] is like a circus,” he adds, “Benjamin pushed back against it because he couldn’t see how he could ever grow beyond it.” When Hubert starting using the line “the world doesn’t need any more chairs” he was trying to “provoke people and be remembered”, according to Fraser.

Hubert decided that “diversifying his income” was the best way to run a studio, making sure he could pay salaries and fund the projects he really wanted to do, says Fraser. During the beginnings of Layer, Hubert realised that almost 25% of the work it was doing was royalty based and essentially done for free before seeing any profit.

By taking on fee-paying work, Hubert was able to fund pro bono projects for social causes with a more beneficial outcome, such as the Maggie’s charity Change Box and the Carbon Trust project in 2015. For start-up companies with low cash flow, Hubert accepted a smaller fee plus equity in the company, finding that “having a stake in it” motivated him more, Fraser adds.

Providing the full package

Hubert has always been “clever” about how he “packaged himself as a designer,” says Fraser, adding that he is always prepared to do a lot of “groundwork” before coming to the design of a product. In a bid to “create better work with more integrity”, he says that Hubert gradually merged his role as a designer with the role of art director, becoming involved in everything “from the communication and photography through to the branding” as well as the design.

Fraser explains that Hubert’s extended involvement stemmed from his earlier frustration with “only being a product designer and not having a say in how a thing was packaged, branded or marketed”.

While this “holistic approach” is not unique to Hubert, Fraser believes that he has truly embraced it in in his practice. This is also why Hubert is “keen to employ permanently” rather than hire freelancers, says Fraser, because he likes people to be “committed to his cause”.

“The monograph Layer is a marker in the sand of what Benjamin has achieved to this moment and the next book may well look very different,” says Fraser. He adds that Hubert’s ultimate message to a designer coming into the industry would be: “Question things all of the time and don’t take anything as a given if you can see another way”.

Source: designweek.co.uk